Upgrading the Africa-EU Digital Relationship

TikTok Hit with Child Privacy Lawsuit

August 9, 2022

How to Stop your Kid from Making In-App Purchases

August 9, 2022

Teki Akuetteh

Founder & Executive Director, Africa Digital Rights’ Hub

Michael Pisa

Policy Fellow

This blog is part of a series by CGD ahead of the EU-Africa Summit which will begin on 17th February 2022. This series presents proposals for priorities and commentary on whether a meaningful reconstruction of the relationship between the two continents is likely.

Greater integration of Africa and the European Union’s (EU) digital markets would be a boon to both regions. But to achieve this, both regions would have to adapt. For Africa, this would include promoting digital market integration across the continent by creating more consistent legal frameworks and strengthening the institutions needed to govern the digital transformation. For the EU, it would include establishing a more transparent approach to assessing GDPR adequacy.

How data moves across borders is an increasingly important element of international diplomacy and economic relations, reflecting data’s growing value and the potential for its misuse. National policymakers must balance their desire to secure access to digital markets abroad with concerns about how data generated in their own jurisdictions can be misused by foreign actors. A growing number of countries have sought to strike this balance through cross-border digital economy agreements that seek to harmonize regulations across countries.

The case for closer digital market integration between Africa and the European Union (EU) is compelling for both regions. European companies would benefit from tapping into Africa’s fast-growing Internet economy—which could grow to $180 billion by 2025—while African companies could more easily access consumers in the world’s third largest economy and engage with a European tech scene that seems poised for faster growth.

Increasing the size of the digital export market for firms on both continents is important because Africa and Europe lag far behind other regions in creating domestic digital champions. Companies in Africa and the EU combined account for only 5 percent of the global value of digital platforms, compared to 67 percent accounted for by companies in the Americas and 29 percent in Asia (UNCTAD 2021 Digital Economy Report, using data from Holger Schmidt).

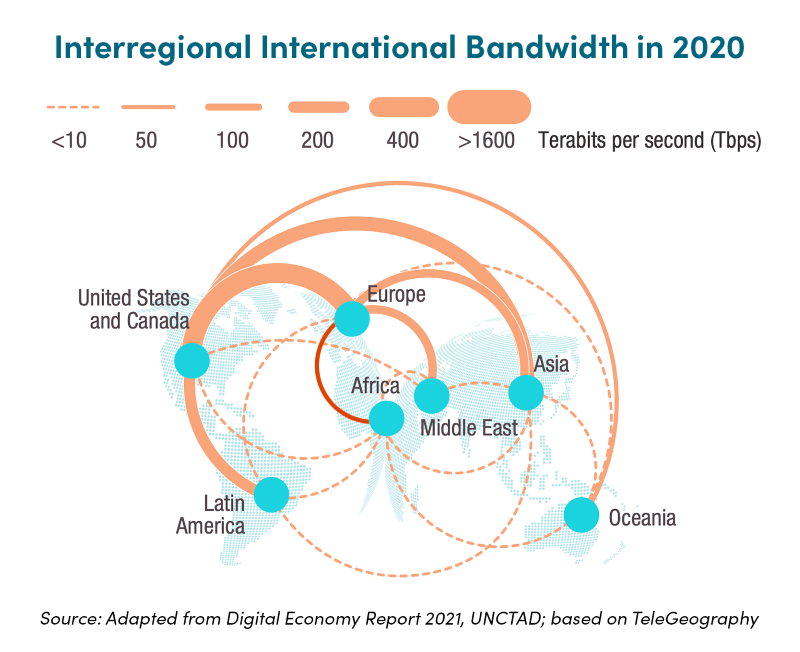

The regions’ proximity also lends itself to closer digital trade ties. As with trade in physical goods, the level of digital services traded among country pairs decreases with distance. So it’s not surprising that the volume of Africa’s cross-border data flows with the EU is greater than with any other region (with the caveat that the volume of flows is an imperfect proxy for their value. See UNCTAD 2021 Digital Economy Report for a discussion of this metric).

Overcoming barriers to digital integration

The African Union (AU) and EU have established several initiatives to deepen digital cooperation, including the AU-EU Digital Economy Task Force, which supports digital transformation and market integration within Africa, and the AU-EU Digital Cooperation Agenda, which promotes policymaker dialogue, knowledge-sharing, and technical assistance across the two regions.

Upgrading the AU-EU digital relationship from cooperation to integration would require policymakers from both regions to agree on rules and standards for governing data use and cross-border data flows. But reaching agreement may be complicated by the regions’ different starting points in their level of digital development, the depth of their regulatory frameworks, and the clarity and cohesiveness of their visions for governing and nurturing the digital economy.

The EU is home to the world’s most advanced regulatory framework for data, with years of jurisprudence behind it. Building on the global influence of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), EU leadership has set out an ambitious and far-reaching agenda for the next decade to promote and regulate the Digital Single Market and further shape digital standards abroad. This agenda includes proposals like the Digital Services Act, Digital Markets Act, the Data Governance Act, and, most recently, the Artificial Intelligence Act.

Africa’s approach to data governance has already been shaped by the EU’s influence, as all 25 African countries that enacted new data privacy laws over the last decade modelled their approach on the GDPR and DPD to some degree. But the evolution of data and digital governance models across the continent is uneven. For example, eight years after the AU’s adoption of the Malabo Convention—which sought to establish a regulatory framework for cybersecurity and personal data protection—only 14 countries have ratified the agreement and roughly half of the continent’s 54 countries lack any form of data protection law at all. Even where data protection laws have been enacted, efforts to implement and enforce those laws are nascent and many African data protection authorities lack the resources and autonomy needed to perform their job effectively.

Whether a framework for governing data developed by EU policymakers for the EU is the best model for Africa, a region with greater institutional diversity and greater resource constraints, and whether African policymakers want to embrace a framework that some industry groups and EU MPs have criticized as creating barriers to useful innovation remain open questions.

Working towards a relationship of co-equals

As the AU-EU Digital Economy Task Force notes, a stronger digital economy partnership between Africa and the EU must be developed on “equal footing”, based on mutually beneficial agreement. This will require policymakers in Africa and the EU to adapt.

Africa: Developing a coordinated strategic approach

Developing a single African digital market with harmonized data policies across the continent would help African tech companies compete at home and abroad and strengthen the AU’s negotiating power relative to global tech companies and other jurisdictions, including the EU.

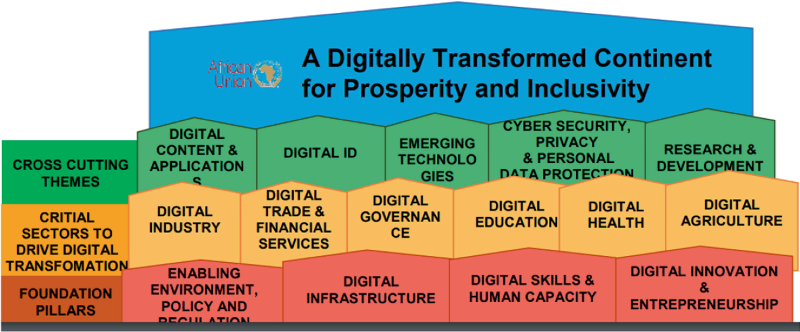

Efforts to build towards this aim are gaining momentum. The AU’s Digital Transformation Strategy sets the aim of creating a Digital Single Market by 2030 in line with Africa’s Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and contributing to its Agenda 2063, which “envisions Africa as a continent on equal footing with the rest of the world as an information society [and] integrated e-economy.” Importantly, these efforts seek to bolster Africa’s role as a producer of digital goods and services rather than its often-assumed position as a mere consumer.

While the AU’s strategic vision for Africa’s digital transformation identifies broad cross–cutting themes, critical sectors, and foundational pillars, it does not provide a clear agenda for prioritizing reforms or investments in the near-term. This would lessen the risk that digital Africa will become a “jack of all trades and master of none.”

The largest barrier to developing a single African digital market is inconsistent national rules across all facets of digital governance, including e-commerce laws, consumer protection laws, privacy and data protection laws, and cybercrime laws. Inconsistent rules are a problem for African tech companies seeking to expand beyond their domestic markets, which puts them at a competitive disadvantage. The challenge for the AU will be to harmonize laws in these areas while accounting for the differing aims and levels of digital development of its 55 member states.

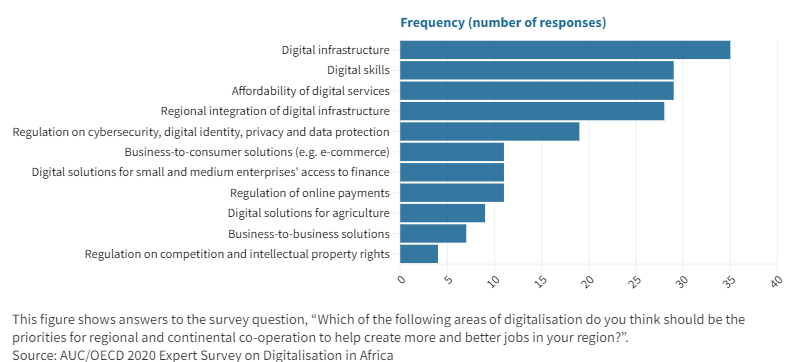

The creation of more consistent legal frameworks must be matched by efforts to strengthen the institutions needed to oversee the digital transformation process (including data protection authorities and agencies overseeing cybersecurity and e-commerce), improve coordination among continental institutions supporting the digital agenda, and create a stronger foundation in digital skills and infrastructure (respondents to a recent survey by the AU and OECD cited digital infrastructure, digital skills, and the affordability of digital services as the key priorities for regional and continental digital cooperation). To convince policymakers of the importance of dedicating greater resources and political attention to these efforts, the AU has announced a communications strategy geared towards achieving “buy-in of the public sector to the digital strategy, and to promote the importance of digital transformation.”

European Union: Rethinking the approach to GDPR adequacy

The global influence of the GDPR puts the EU in a strong position when negotiating with other jurisdictions over data policy. It also underscores the importance of EU’s process for determining whether another country has an “adequate level of protection essentially equivalent to that ensured within the Union.” Although other means of establishing legal cross-border data flows with the EU exist (such as standard contractual clauses), an adequacy determination confers a competitive advantage because companies based in countries that receive it face lower costs to doing business with EU citizens.

To date, no African country has received an adequacy determination and digital policy experts from the continent have expressed concern that the process for determining adequacy is excessively opaque and often appears to be driven by political and economic considerations, rather than the fitness of a country’s data protection regime. The risk is that failure to achieve adequacy could set countries already behind on their digital transformation journey even further back.

While all governments should be free to determine the basis on which the personal data of its citizens can be shared abroad, the EU has a special responsibility in making the GDPR adequacy process transparent because of its aim of setting a global standard. The European Commission should make the process as transparent as possible, including by publicly stating why decisions are denied or delayed for certain countries. Similarly, EU leadership should champion an outcomes-based approach to establishing adequacy that focuses less on the form of a foreign country’s data protection framework and more on its effect.

Policymakers attending the EU-AU Summit should celebrate the cooperation achieved to date and set their sights on making greater digital market integration a reality.

RELATED TOPICS:

DISCLAIMER

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.